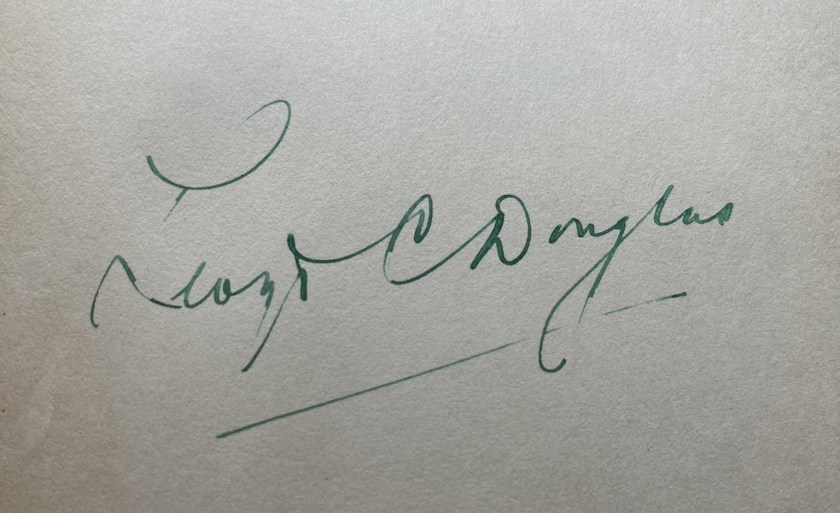

This is an excerpt from the sermon, “Personality (Third Phase),” preached by Lloyd C. Douglas at the First Congregational Church of Ann Arbor on February 1, 1920. (In Sermons [5], Box 3, Lloyd C. Douglas Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan. © University of Michigan.)

“There is also that tendency in middle life to slide. After the senses have become jaded, after the bloom has been rubbed off the ideals and anticipation holds out fewer dazzling fingers, then comes the menace of what an old-time bard called ‘the destruction that wasteth at noonday.’

“There was Saul. I would not weary you with a long story. Just a few broad charcoal strokes will suffice; a mere silhouette of him.

“His nation wanted a king. Saul was a brawny youth, handsome as any Terrean ever was. Head and shoulders over any other young man of his generation. And when the old judge, who had it all to say who should be appointed king, spied this super-youth, he called his long quest ended, invited him to an interview, told him to go home and wind up his affairs, and prepare to wear his nation’s crown.

“And Saul was completely overpowered by the high distinction that had come upon him, right out of the blue. He was afraid he wasn’t quite up to the part. Indeed, he hid himself among the freight of the caravan, half-inclined to ‘beat it,’ as we say, and evade the terrific responsibility. But persuaded at length that it was his duty to obey the call to kingship, he acceded to the throne, robed himself in the vestiture of royalty, and looked — and for a time acted — every inch a king.

“The years passed. Saul concentrated more and more upon the interests of his court as against the larger interests of his kingdom. More and more he took on the role of an autocrat, aristocrat — less and less the attitude of service to his nation. Little by little he came to regard with jealous hatred every strong personality in his court. Even the shepherd lad, brought in to play for him upon the harp, excited Saul’s envy until he was filled with murderous rage. Until, bye and bye, it was said of him, in curious words which are spoken in a tone of bleak finality, his spirit left him. And then the chronicler observes, ‘But Saul wist not that his soul had departed from him.’

“It was gone, but Saul didn’t know it. He didn’t miss it. He still had his crown; his scepter; his ermine — or whatever was the equivalent of ermine in Saul’s regal establishment; but his soul was gone.

“Where? How? When? Nobody could say.

“He had just aped the tawdry pomp of his heathen contemporaries a little too long. He had just allowed his own interests to outweigh his vested responsibilities a little too far. He had allowed his soul to come out of him gradually, until there was nothing left of it — even if he wist not that it had departed from him.

“If you have never read this majestic poem which recites the details of Saul’s tragedy and the Nemesis that overtook him, do not much longer deny yourself that experience. I do not mean to narrate any more of it. Just to stamp this one sentence down hard upon your consciousness: ‘And Saul wist not that his soul had departed from him.’

“How many a man who, as a youth, was visited by splendid dreams of a future made bright by loyal friendships, worthy achievements, and the reasonable rewards of fair deeds, has drifted and drifted on toward the twilight of age — morose, dissatisfied; both hands full of gold, perhaps; barns filled with corn, perhaps; ready to eat, drink, and be merry — and when his soul is required, he finds that he hasn’t a soul. It has departed, though he may not have observed its flight.

“And since we have been standing for a moment before an old-world portrait, let us tarry in this closing moment before another. The great emancipator of this same nation has been up on a hillcrest to commune with God concerning his responsiblity as a leader. The whole nation has been waiting in the valley for his return. And when he came down and rejoined them, it was said of him that his face was illumined. And the historian adds, ‘And Moses wist not that his face shone.’

“He was reflecting the glory that was his by virtue of his spiritual contact with his Father, but he didn’t know that his face shone. If he had known it and had thought about it and had prided himself on this distinction, perhaps the strange light would have departed from his eyes. But he was unaware of it, simply because he was too much wrapped up in the love he bore his people, and his sense of high obligation to serve them.

“I think we shall find it true that most men and women who are able to exercise great power over their fellows wist not that their faces are illumined. And just because they do not know it — being too much engrossed with the duties thrust upon them to love, to serve, to lift, to heal, to redeem — their faces shine.”