Sometimes the little things end up being important later, even if we don’t notice them at the time.

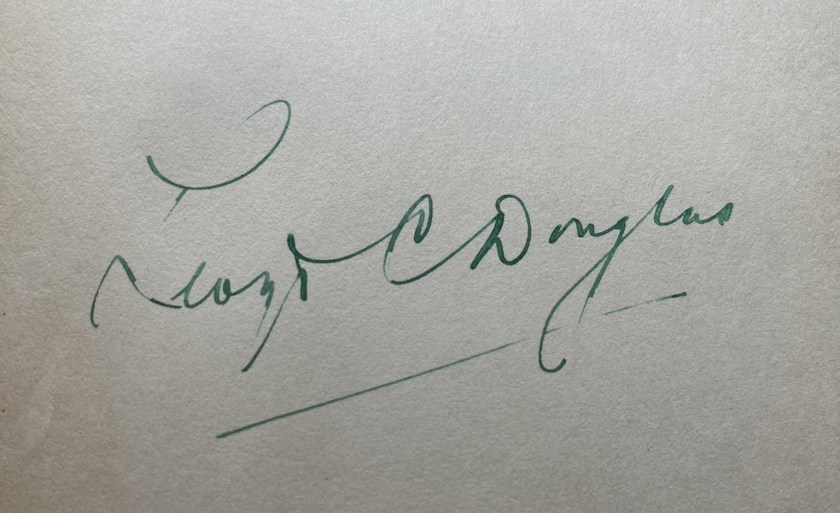

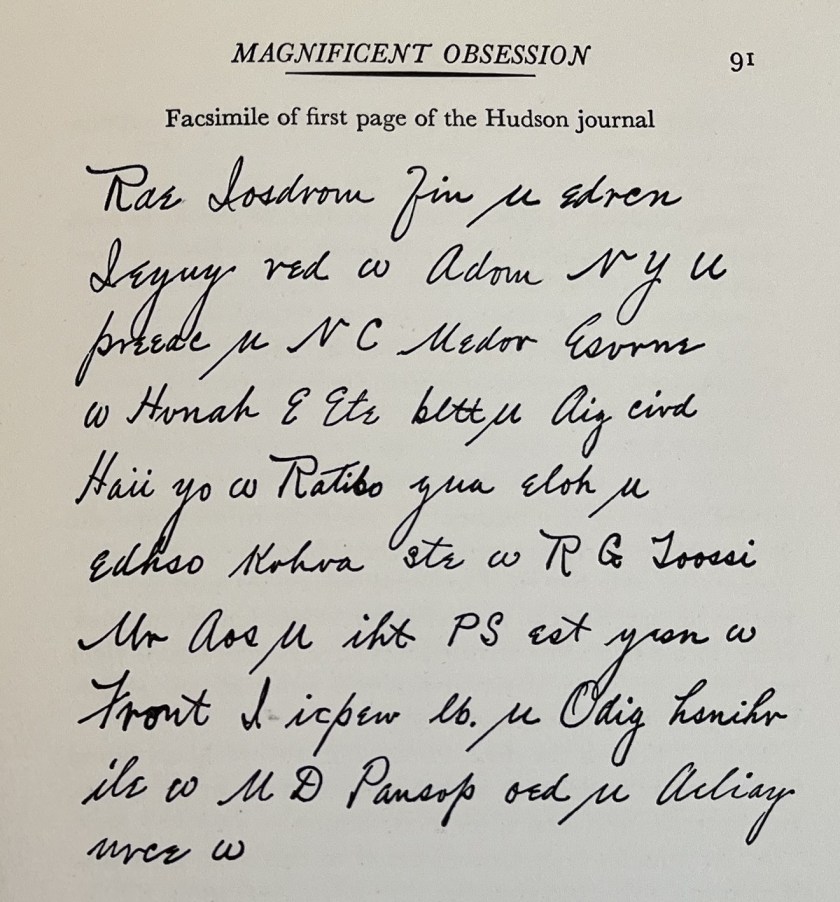

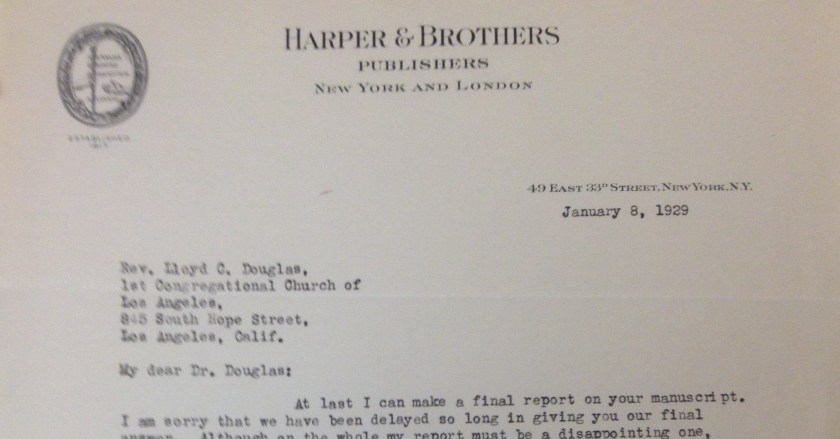

In Lloyd Douglas’s case, it was a mere phrase he happened to utter in one of his sermons ten years before the publication of his bestselling novel, Magnificent Obsession. The title of his sermon was “The Pearl-Trader,” and he delivered it at the First Congregational Church of Ann Arbor on October 26, 1919. (It can be found in Sermons [4], Box 3, Lloyd C. Douglas Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan. © University of Michigan.)

The phrase I’m talking about was: “If we may be permitted to lend our imagination wings…”

His biblical text was Matthew 13:45-46, which says, “The kingdom of heaven is like unto a merchant seeking goodly pearls; who, when he had found one pearl of great price, went and sold all that he had, and bought it.”

There doesn’t seem to be much meat in that short passage, but Douglas used his imagination to make more out of it. From a strictly exegetical point of view, one may argue that he should stick to the text; but from a biographical point of view, the fact that he indulged his imagination on this occasion is significant. And, unlike the average pastor, Douglas’s imagination always produced interesting results.

He says of the pearl trader: “If we may be permitted to lend our imagination wings, we may venture a guess that he… picked up one of his treasured pearls in Athens, the traditional seat of learning. Perhaps he called it his ‘Agnostic’ pearl. It had a special value for him. It stood for a neutral-tinted, convictionless attitude of mind, forever in quest of truth and never satisfied with its booty; forever asking for evidence, cross-examining witnesses and demanding testimony – and never reaching a verdict.

“Sometimes his heart proposed that he take a definite stand for something; espouse a cause and see it through; join hands with a movement and put it over; announce discipleship to some Master and follow him; but always he remembered the Agnostic pearl and remained non-committal. ‘Skeptic,’ his friends called him, and the word was not an epithet but a badge of merit, to his mind. He liked to be called ‘free-thinker.’ I suppose that of all the pearls he had, the merchant loved this one best.”

A lot of people in the church that day could probably empathize with this position – especially freshmen. Douglas continued:

“But not much less ardently did he rejoice in the possession of the flawless pearl he had bought in Rome, the headquarters of jurisprudence. Whatever qualms of conscience the Agnostic pearl aroused in him, this Roman stone, which he called the Justice pearl, stirred him to a self-righteous pride. For Justice was an undeniably fine attribute for any man to possess.

“Sometimes his heart suggested that he waive aside the claims of inexorable justice and invest something in behalf of human woe and wretchedness – even if that misery had but little to justify it. Sometimes he would have been glad to do something, out of the charity of his heart, for a weaker fellow; but always he remembered the Justice pearl. Every man should have exactly his due from him, and no more. Mercy was enervating. Mercy was always wearing its heart on its sleeve and getting itself taken in by imposters. No; Justice would do for him.”

Personnel from the administrative side of the University of Michigan were there that morning, and perhaps they felt the same way. Douglas continued:

“And then there was that most showy pearl of the lot, the one he had found in Alexandria, the home of riches and commercial prosperity. As he rubbed his sensitive thumb delicately over its satin surface, he glowed with satisfaction over its ownership. Just carrying it had brought him wealth. After all, honor and influence were not far away from the man who had amassed much property. It was ever so. Poverty, even voluntarily embraced in the interest of a great cause was nevertheless a serious handicap. Not for any consideration would he part from this jewel which he knew as his Prosperity pearl.”

Members of the Ann Arbor business community were members of the church, including prominent business leaders. Perhaps they could relate to this attitude. Douglas continued:

“But with all his goodly pearls he was not content, but still sought others. He appears to have had a haunting suspicion that somewhere there was a valuable pearl to which he had not yet gained access. I daresay he felt it would be a great pity to have gone through life, bent upon the exclusive business of finding the most valuable pearls, and then discover, perhaps when it was quite too late to achieve it, that the most wonderful pearl in the whole world was not his – could never be his – that he had not even seen it, much less owned it.

“It is this gnawing unrest that brings many of us toward the day of silvering hair and faltering footsteps, fearful that, after all, try as we might to live purposefully, we had somehow missed the very best things – maybe passed them, unnoticed, along the way; maybe tossed them aside, as of no account, in our ignorance of their value. Indeed, the man of fifty sometimes reflects that he remembers the day when he passed a great opportunity to possess something of inestimable worth; and if he might set his life back as easily as we set back our clocks last night [for the fall time-change], he would surely want to go back to that crucial hour and live it again.

“I do not know just how much this pearl-merchant worried lest he was rejoicing in the possession of some second-rate jewels when he was seeking the very best; but I do know that when the Master introduces him to us, he is still seeking pearls, goodly pearls. Still touring about from country to country, by ship and caravan, seeking better pearls than these he owned. It doesn’t look as if he was entirely contented.

“You will find them all along the way, many of them people you have envied for their conspicuous positions, their learning, their culture, their wealth – you will find them, like the pearl-merchant, still in quest of something better than they possess. Restless souls, whose very quest proclaims their dissatisfaction with their accretions.”

We know, of course, that the Pearl Merchant is going to find that one pearl that will outshine the others. But Douglas indulges his imagination in other ways, and what he does next is very interesting. I’ll tell about it in my next post.