“[Y]outh is by nature in a state of revolt. That is as it should be…. It is in the interest of progress that each new generation shall have its moments when father is fine, but a fogy, and mother is well-meaning, but obsolete.”

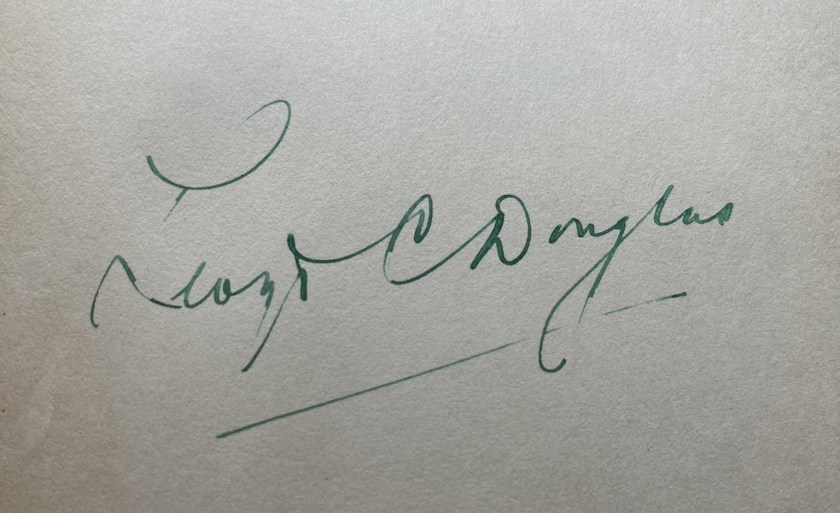

Lloyd Douglas is preaching at the First Congregational Church of Ann Arbor, adjacent to the University of Michigan. The date is October 12, 1919. (I’m quoting from Douglas’s typed script in Sermons [4], Box 3, Lloyd C. Douglas Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan. © University of Michigan.)

“An occasional pioneer may go out into a new and unknown country, led by the lure of strange adventures, gambling on finding a more enjoyable and prosperous life. But most pioneers go out because they have found their old conditions intolerable.

“Youth does not often announce that it proposes to pursue a new course of thought for the sheer love of adventure with the untried. He can offer a much better reason than this for his pilgrimage. He is dissatisfied with things and thoughts as they are. He is not an immigrant, but an emigrant. He is not searching for anything; he is discarding something. He wants to shake himself free of the restrictions which fetter his spirit. No sooner has he escaped his parental prison than he begins to rebel against the old authorities, and at a very tender age, sets up his will in defiance to the will of those who have custody of his childhood. In school, he considers it part of his life program to annoy his teachers and break their rules….

“Much of the scheming and plotting indulged in by college students, to deceive their instructors and slight their academic duties, does not indicate a desire on their own part to deny themselves the mental training which they have sacrificed many a pleasure to secure, so much as an inherent passion to escape the conventional restrictions imposed upon them by their elders.

“Frequently we deplore the overemphasis placed upon athletics and social diversions by students who, in the natural course of things, should be giving the best of their energy and ingenuity to their studies…. Perhaps it would be a pleasant experiment to devise a college course made up on athletics all forenoon, dances all afternoon, and compulsory movie-shows at night. It would be of great interest – would it not? – to see some people you know, possibly including yourself, begging an honest man to answer your name at roll-call at the hop, in order that you might steal to your room and snatch a few pages of economics.”

(Eyewitnesses say that the congregation often laughed out loud at some of the things Douglas said from the pulpit. Perhaps this was one of those times.)

“But we may as well be honest with each other,” he continues. “You have your duty to perform, and that duty demands that you shake yourselves free, so far as possible, from any restrictions which fetter the full development of your life. And we have our duty to perform as elders, also in obedience to an instinct over which we have little control, to see to it, with might and main, that you do not go too far or too fast in your revolt. Your generation constitutes the main-spring, and our generation constitutes the escapement-wheel. If it weren’t for you, there would be no more power promised; and if it weren’t for us, you would dissipate your energy to no purpose.”

To what purpose, then, should the students in this auditorium devote their lives? Yes, they must launch out in their own way, leaving the past behind, but to what specific purpose? That would be for each of them to decide for themselves, but whatever quest they choose, they must ask themselves what role religion will play in it.

“Not only is it laid upon the potential leader of the day that he shall approach this subject [of religion] with becoming seriousness, but that he shall be able to contribute certain constructive opinions as to what type of religious thought may best answer the needs proposed by the peculiar conditions at work in modern times.

“It is extremely doubtful if the professional clergy, enmeshed in their ecclesiastical traditions, and under the duress imposed upon them by the denominational authorities to whom they feel themselves obligated, can ever hope to do for religion what you may accomplish who, as influential laymen, will be in a position to contribute your thought, independent as you are of these restrictions and constraints.

“All this deepens the collegian’s responsibility to inform himself concerning the history of religion in the world, awake to its blunders and delinquencies as well as to its benefits and achievements, with the hope that it may repeat its triumphs and avoid the repetition of its failures.”

Douglas has been saying that the inherent rebelliousness of youth should be put to good use, studying the history of religion in order to help guide it in the immediate future. In the last part of his sermon, he will challenge the students in the balcony to take this responsibility seriously.