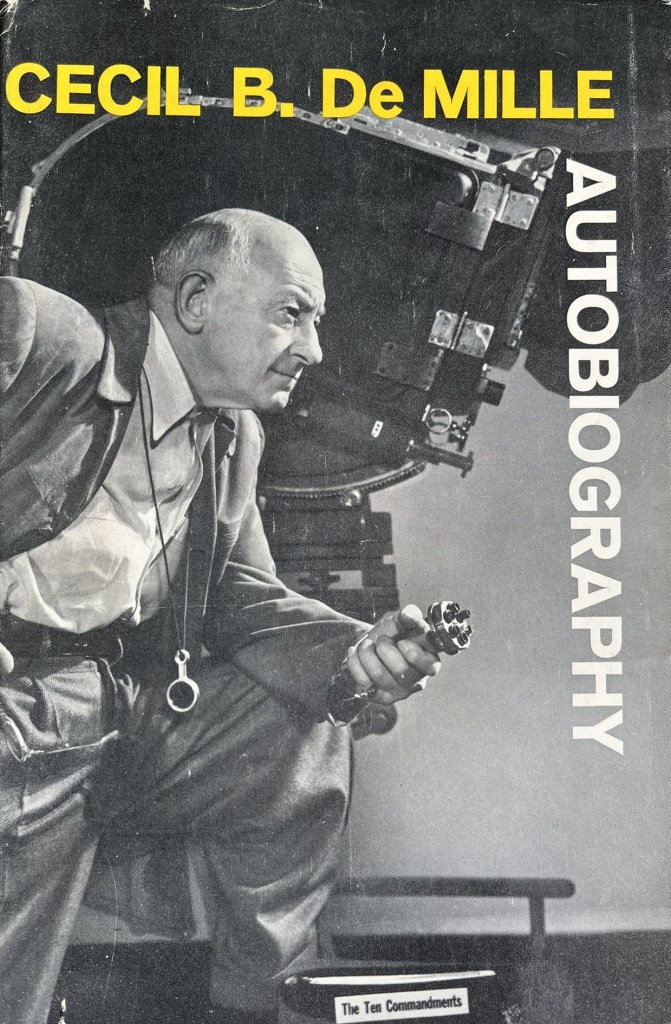

I’ve been telling you about the work Lloyd Douglas was doing on his novel, Salvage, during the summer of 1928. But that same summer he also clashed swords publicly with filmmaker Cecil B DeMille. I’ll tell you about their public disagreement in a later post, but for the next two posts I want to give you some background, for Douglas had already written about DeMille a year before they ended up in the newspaper together.

In the summer of 1927, De Mille’s The King of Kings was in theaters around the country. It was a two-and-a-half hour silent film, but for its day it was quite a spectacle.

Much of the dialogue was straight from the scriptures, and the chapter-and-verse citations were even included; but the scriptural context was often disregarded. Events and quotations were all jumbled up, like a weird black-and-white dream. After Jesus cleanses the temple, the crowd tries to make him king (confusing that scene with events in John 6), so he escapes to the top of the temple and then (again out of order) is tempted by the Devil. Early in the film, Simon Peter speaks to a young boy and says something straight out of one of the Epistles of Peter – written decades later.

The way Christ is introduced is interesting, but also a bit confusing. We see his disciples talking to him, but we don’t see him. Then a blind child is brought to him to be healed, and the screen goes black, showing us what the child sees. When the child’s eyes open, we see a bright light, which dissolves into the smiling face of the well-known silent-movie actor, H. B. Warner. It takes a moment to realize that he’s actually supposed to be Jesus. “Oh… okay then.”

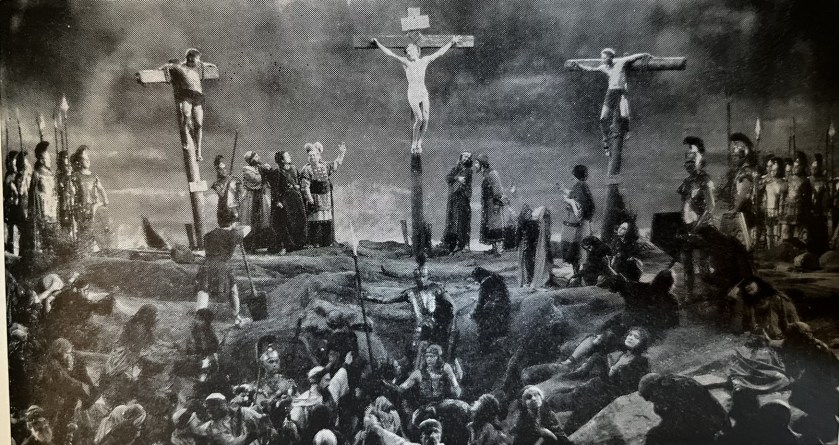

It’s also rather distracting, at Christ’s crucifixion, to note that the thieves on either side of him aren’t nailed to their crosses; they’re just tied to them, and they don’t look like they’re going to die anytime soon.

But still, for its time it was quite a spectacle. Lloyd Douglas thought so, too. He wrote an article about it in The Christian Century (Lloyd C Douglas, “The Gospel According to De Mille,” Christian Century, 7/14/1927). The fact that Douglas was the pastor of the First Congregational Church of Los Angeles made the essay seem like on-location reportage, although it wasn’t.

Of DeMille himself, Douglas was highly complimentary: “Not only does this man know his New Testament, but he has ransacked the entire lore of that era. If the average preacher gave himself with as deep concern to the business of revitalizing the story of Jesus and his times, churchgoing would be vastly more rewarding.”

Of the film’s depiction of Jesus, however, Douglas was critical: “One is conscious, throughout the whole spectacle, that one is seeing the traditional Roman Catholic conception of a Christ who has come to earth primarily to die. Let all the people about him do or leave undone whatsoever they will; befriend or harass; condemn or crown; he is here to die—and everybody is waiting, nervously, for the tragedy. Jesus, in the picture, moves about slowly and sadly, with the air of one already unjustly convicted. Now and again, there is a gesture of futility more reminiscent of Omar Khayyam than Jesus of Nazareth…. The shadow does not lift….

“Persons who think of Jesus as the world’s master teacher, chiefly concerned with the spread of a new message of hope and joy, the promotion of victorious idealism, the development of a broader altruism, the building of a kingdom of heroes, are not quite content with so supine and languid a Christ as the abstracted, detached, time-marking, sighing Jesus who dominates the stage in ‘King of Kings.’”

Douglas liked the film’s depiction of the miracles. He felt it demonstrated just how ridiculous it was to picture Jesus as a worker of wonders. He hoped that “Persons who have been uncertain whether the magician-Jesus is quite adequate to deal with the baffling problems of these modern times, in which there is so little room for necromancy in the thought of intelligent people, will be encouraged by ‘The King of Kings’ to make a fresh examination of the essential character of Christ.”

Overall, Douglas gave the movie high marks, considering the fact that De Mille’s views were conservative and Douglas’s were liberal. Over the next several months, however, he became more critical of the film. I’ll talk about that in my next post.