Over the last dozen posts I’ve been talking about Lloyd Douglas’s work on a novel called Salvage during the summer of 1928 (what would later become known as Magnificent Obsession) and of Harper & Brothers’ attempts to make sense out of it. Douglas had put two very different genres together: a novel (specifically, a hospital drama) and a non-fiction treatise about the first few verses of Matthew 6.

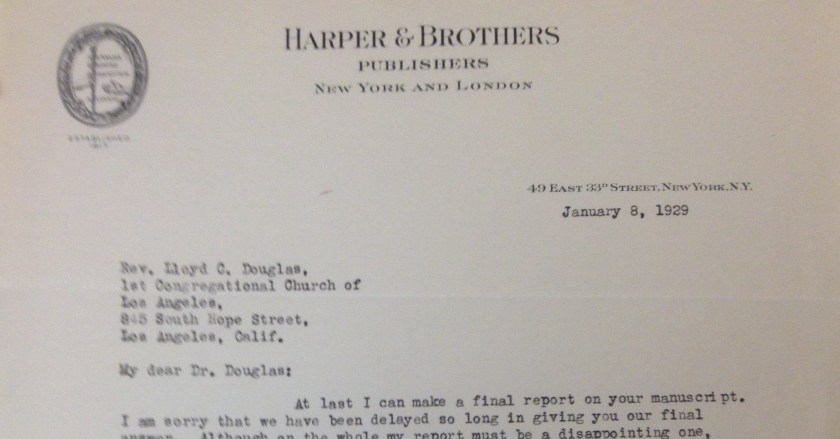

In January 1929, Eugene Exman, Harper’s religion editor, gave Douglas his company’s verdict. Four members of the Literary Department had read the updated version and recommended against publication as a novel. They categorized it “between the manuscripts that were almost good enough to publish and those which were obviously important enough to publish.” In his earlier correspondence, Exman had used words like “good enough” and “important enough” to assess the book’s marketability, not its literary quality. Years later, he would claim publicly that the head of the Literary Department considered the book “second-rate fiction and not deserving of the Harper imprint,” but nothing was said about that in his letters at the time. If it was true, however, then it added an extra layer of complexity to Douglas’s task: although he was using fiction techniques to communicate his message, he was under no illusion that he could be regarded as a serious – much less, first-rate – novelist. That wasn’t what he was trying to do at this stage in his career.

True to his word, Exman then tried to publish the book as religious non-fiction. As Harper’s Religion Editor, he had the authority to do that. In retrospect, it seems like a strange move, since Douglas had clearly written the book in novelistic form; but if it was a choice between treating it as a religious book or not publishing it at all, Exman chose the former. But first, he had to get the opinion of an expert.

He sent the manuscript to an anonymous but “prominent” churchman. I’m going to hazard a guess here: it very well might have been Harry Emerson Fosdick. I say that for two reasons. First, because Exman was then a member of Park Avenue Baptist Church, where Fosdick preached while Riverside Church was being built for him. Second, because Exman was patiently trying to win Fosdick over to Harper from Macmillan, and he eventually succeeded. They published 17 books together. (Stephen Prothero, God, the Bestseller: How One Editor Transformed American Religion a Book at a Time (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 2023), p. 41).

But whether I’m right or not, Exman showed the manuscript to some “prominent” churchman, who in turn shared it with three other “very discerning people.” The clergyman rejected the book’s thesis and advised against publication on theological grounds. And with good reason, one might argue. The book seemed to promise worldly success. A lot of explaining would be necessary to translate the story into anything resembling traditional Christian theology. That was Douglas’s intention, of course: to speak the language of the unchurched and get them interested in Jesus without sounding like a preacher. But the prominent churchman that Exman consulted was unwilling to go along with it.

“Whether his point is well taken is not of such great importance,” Exman told Douglas. “The thing which concerns me is that the publication of the manuscript would not get his backing as well as the backing of the group in the church he represents.” Once again, the main obstacle was economic. Exman had reason to believe that the book wouldn’t sell.

In brief, then: Harper had carefully considered publishing the book, but the editors were uncertain whether it could meet their sales goal. Would it do better as a novel or as a religious tract? Their answer was, Neither.

Douglas had hoped to present the Christian gospel in practical terms and to spread his message to an audience far beyond the confines of the church. His book was an experimental piece of writing that could possibly help him attain that goal, but “possibly” was the operative word. Eugene Exman realized that the book was unusual, but he lacked evidence that the general public would recognize its worth. Without that assurance, he could not take the financial risk. “I really believe that it should be published,” he told Douglas, “although this may seem a paradoxical statement; I am sorry the imprint of our House will not appear on your book when it does go out.”

The situation was paradoxical indeed, for Eugene Exman, perhaps more than any other religion editor, went on to publish the books that would both create and give direction to what we now call the SBNR movement (Spiritual But Not Religious). Late in his career, he considered Douglas’s book the one that got away (Prothero, p. 276).