When Lloyd Douglas was living in Ann Arbor and learning about surgery at the University of Michigan’s medical school (sometime between 1915 and 1921), he read a notice in the newspaper that he thought would make an interesting premise for a novel. A physician had drowned while the inhalator that could have saved his life was being used on a young man who had been in a boating accident. Douglas clipped the article out of the paper and carried it in his wallet for years. After thinking about it for a long time, he started writing that novel in 1927. Its working title was Salvage.

He didn’t get very far into it before he realized that the idea by itself wasn’t substantial enough for book-length treatment. In the first chapter he introduced his main characters – Dr. Wayne Hudson, a world-renowned brain surgeon who is also the founder of Brightwood Hospital; his grown-up daughter Joyce, who parties at all hours with her friends, including the rich young playboy, Bobby Merrick; and a young woman named Helen Brent, who is a positive influence on Joyce and, for that reason, has agreed to marry Dr. Hudson and help bring order to their home. At the end of the first chapter, young Merrick, who is drunk, falls overboard in a sailing accident and is revived by Dr. Hudson’s inhalator, just as the doctor himself is drowning and in need of the device.

In Chapter Two, Bobby Merrick wakes up at Brightwood Hospital, where he discovers that his life has been saved at the expense of Dr. Hudson’s. Although he feels bad about it, he doesn’t know what to do. In a heart-to-heart discussion with Brightwood’s head nurse, Nancy Ashford, Merrick decides to make something of himself, so that Dr. Hudson’s sacrifice will not have been in vain. It is implied that, because Merrick has the aptitude for medicine, he will perhaps follow in Dr. Hudson’s footsteps.

And that was all.

In two chapters, Douglas had already accomplished what the clipping in his wallet suggested. The rest would be up to the characters to work out. He assumed that Merrick would go on to medical school… but then… what? Douglas didn’t know. He didn’t even know which way the love triangle would go. Would Merrick end up with Joyce or with Helen?

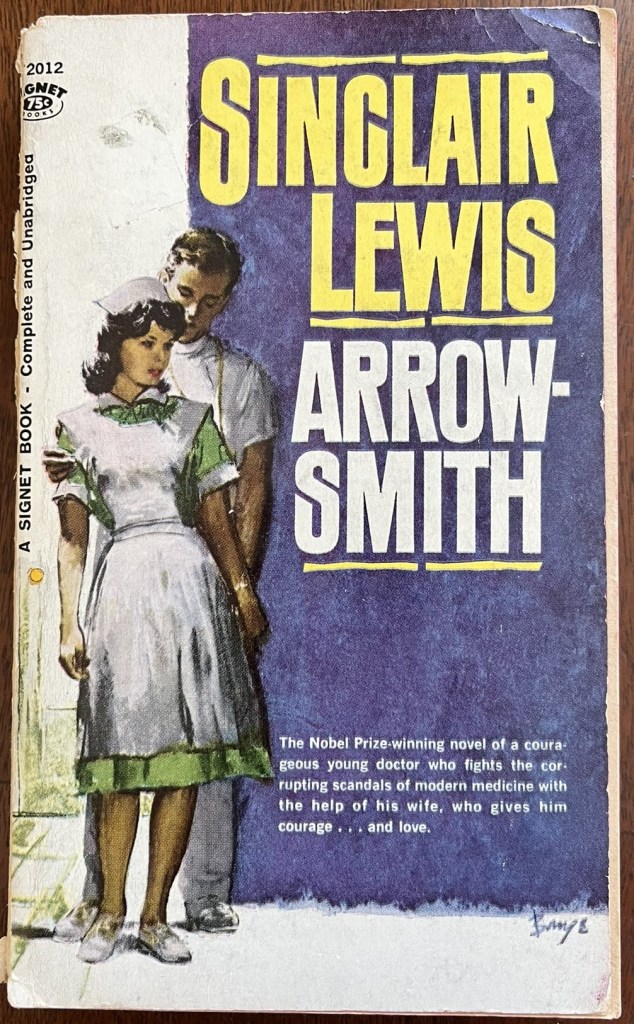

If you’re familiar with this story at all, I want you to forget everything you know about it, because, at this point in Douglas’s life, the proposed novel had a very different feel to it from the story you’re thinking of. What Douglas had in mind, as of 1927, was a completely secular book – something akin to Arrowsmith, the 1925 Nobel-prize-winning novel by Sinclair Lewis.

During the late 1920s, Douglas was watching Lewis closely and even considered him his direct competitor. (This comes out in Douglas’s interviews and correspondence around this time.) Lewis knew nothing about medicine, but he did his homework, then wrote Arrowsmith, about a young doctor who is determined to pursue medicine scientifically, rather than in the old-fashioned country-doctor sort of way. This novel must have touched Douglas on many levels. He, too, believed in the scientific pursuit of medical knowledge, and he must have felt himself more qualified than Lewis to write such a novel. But he also must have been repulsed by Lewis’s young hero, who lacks basic human qualities. Douglas wanted to write a book that would take the reader deep into the scientific aspects of the medical profession, but he also wanted his main character to be a good person, worthy of the term “hero.”

Unfortunately, he couldn’t imagine the rest of the story. What was the point of the book? Why should anyone keep reading after Chapter Two? Douglas didn’t know the answers to these questions. All his life he had been sure – as sure as he had ever been about anything – that he was meant to write novels. And yet this one, once he finally started writing it, came to a screeching halt at the end of Chapter Two. And he couldn’t get past it.

Douglas had other projects to work on while he waited. As I mentioned in the previous post, he had his hands full at the First Congregational Church of Los Angeles, trying to reach professionals and educated people in the city at-large, while being dragged down by some of the core members of his own flock, who were more conservative than any of his previous parishioners had been. This was a big job all on its own. But his latest non-fiction book, Those Disturbing Miracles, was also released at this time by Harper and Brothers, and there were newspaper interviews and correspondence to attend to about that.

And there was something else: he had a big idea for his next non-fiction project. Harper was the top publisher of non-fiction religious titles in America. Now that Douglas had his foot in that door, he was excited about his next non-fiction book. In Those Disturbing Miracles, he had said that faith isn’t merely a belief in supernatural events that happened long ago and far away. To have faith, he said, is to exercise it here and now, by using it to solve the problems of day-to-day life. In this next book, he was going to describe a spiritual adventure in which one could experience the power of God directly… by investing one’s energies in the lives of others and divulging the secret to no one else but God.