In the fall of 1926, Lloyd Douglas began serving as Senior Minister at the First Congregational Church of Los Angeles. He would stay for only two years. (Two years and three months, to be exact: from November 1926 through January 1929.) In their biography of their father, his daughters say repeatedly that he seemed defeated from the beginning, and they are unable to explain why.

I disagree on both points. He wasn’t defeated (although he did resign), and he understood perfectly what went wrong.

I say he wasn’t defeated for two reasons. First, he made a significant impact on the congregation in that very short time and drew to the church people who weren’t interested in it before his arrival. Second, the experience changed his life for the better.

But that’s not my focus today. In this post I want to explain why he had so much trouble working with the congregation.

The answer is complicated. It has to do with the congregation’s demographics, the leadership’s work experience, the membership’s education, and the previous pastor’s inability to let go. (I want to apologize in advance to the current members of the First Congregational Church of Los Angeles. This is not a reflection on you! I’m just trying to explain what happened a hundred years ago.)

Demographics: the congregation was largely made up of rural Midwesterners who had gone to the West Coast to retire. Douglas didn’t mince words. He told his friend William Gilroy, editor of The Congregationalist, “The main trouble with this church and with all the Protestant churches in this city is (this is confidential) they are largely made up of elderly, retired farmers from Missouri and Iowa whose sole experience with the Church has been gathered in the country and small towns. They want a village church here in the heart of metropolitan traffic, and it cannot be done.” Ironically, he continued, the “erotic erratic culture of the movies is in combination with the frumpy, ignorant, fanatical backwash of the rural middle-west.” (LCD to Dr. William Gilroy, 11/19/1928. In Akron 1926 Scrapbook, Box 6, Lloyd C Douglas Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan.)

Work Experience: the leadership of the church was comprised of non-professionals. Again, Douglas didn’t pull punches. To his friends the Van Vechtens, he wrote on 8/4/1927 (“Notes on Douglas Correspondence for Shape of Sunday, II,” LCD Papers, Box 3): “The chief thing that gives me anxiety is the fact that there isn’t a man on my board of trustees who is a person of affairs. The nearest approach to it is the Chairman of the Board, Fisher, who is the Hudson-Essex agent.” A car salesman, in other words. It didn’t help that Fisher was also, according to Douglas, “a doleful pessimist.” “The rest of the board,” he said bluntly, “are retired nobodies – except one Billy Stevens who operates a big laundry and is a boob from Bubonia. Naturally, they are a timid lot of mournful souls – all of them listening intently to whatever complaints they hear to the effect that the church is too extravagant; the preacher too much of a high-brow; the music too classical; and why can’t we have a lot of announcements from the pulpit in the goodole way. And so forth. Fisher brings me my weekly ration of criticism…” Fortunately, in 1928 a new and more optimistic church board replaced the “sourpusses,” and that made Douglas hopeful. But the core of the old-guard members was still difficult to please. They “subscribe frugally and kick lustily,” Douglas said (to Van Vechtens, 2/17/1928, same file).

Education: In the 1960s, as part of his doctoral research on the life of Lloyd Douglas, Richard Stoppe surveyed surviving members of Douglas’s congregations. Although respondents from Ann Arbor and Akron were routinely complimentary of Douglas, respondents from Los Angeles were divided. The positive responses from Los Angeles were “lavish with their praise and on additional pages or the reverse sides of the questionnaires” gushed about Douglas even more than did the people from Ann Arbor and Akron. The negative respondents, however, complained that “he was too liberal and he used too many big words.” Stoppe says that it is clear from “the content, syntax, and vocabulary” of these responses “that those from Los Angeles who disliked Douglas were uneducated. On the other hand, those who praised him were mostly college graduates, several being doctors, lawyers, or dentists.” Those who didn’t like Douglas called him “a show-off trying to impress people with his learning” (Richard L. Stoppe, “Lloyd C. Douglas.” PhD diss., Wayne State University, 1966, pp. 239-240).

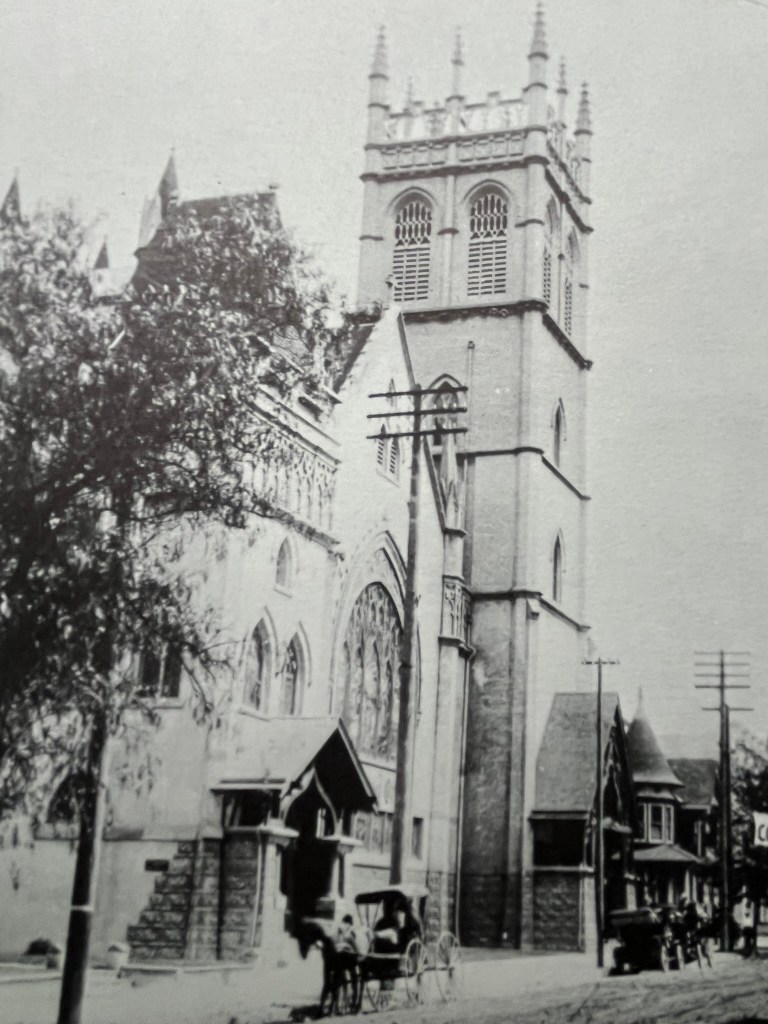

Meddling: The previous pastor couldn’t let go. Dr. Carl Patton had been Senior Minister at the church for nine years before Douglas arrived (1917-1926). Douglas thought the two of them were friends. Patton had preceded Douglas at Ann Arbor, too, and there was never any problem there. Los Angeles was different, however. As Douglas told the Van Vechtens (n.d., “Notes… II”), “…it rather upsets the equilibrium of things when a former prophet comes plunging into his successor’s work. It isn’t so good. I know. Patton came out here in April and has been in and around these parts ever since. It is disturbing, and makes everybody restless. Incidentally, I think his attitude toward me and my work has been unpleasant. He hobnobs with the few families who do not like my style; and messes in my parish. Not very sporting of him!” Douglas was right to worry: Carl Patton would end up replacing him at First Church and serve as Pastor again from 1930 to ’34 (Davis, Light on a Gothic Tower, pp. 84-86, 92-95).

As I said earlier, Douglas was shockingly direct when diagnosing the problems he faced. I’m quoting from private correspondence, and in one case he even said, “This is confidential.” But ironically, what happened in Los Angeles became a part of history, for in his spare time, Douglas did something of more lasting importance than his work with a local congregation.

In 1927 he began writing a novel.